This July is set to be the hottest month ever recorded on Earth—and likely the hottest in about 120,000 years—preliminary analyses show.

With just a few days left in the month, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), the European Union–funded Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) and Leipzig University in Germany have combined temperature data for July 2023 so far with projections for the remainder of the month and have found it will be the hottest July by a wide margin.

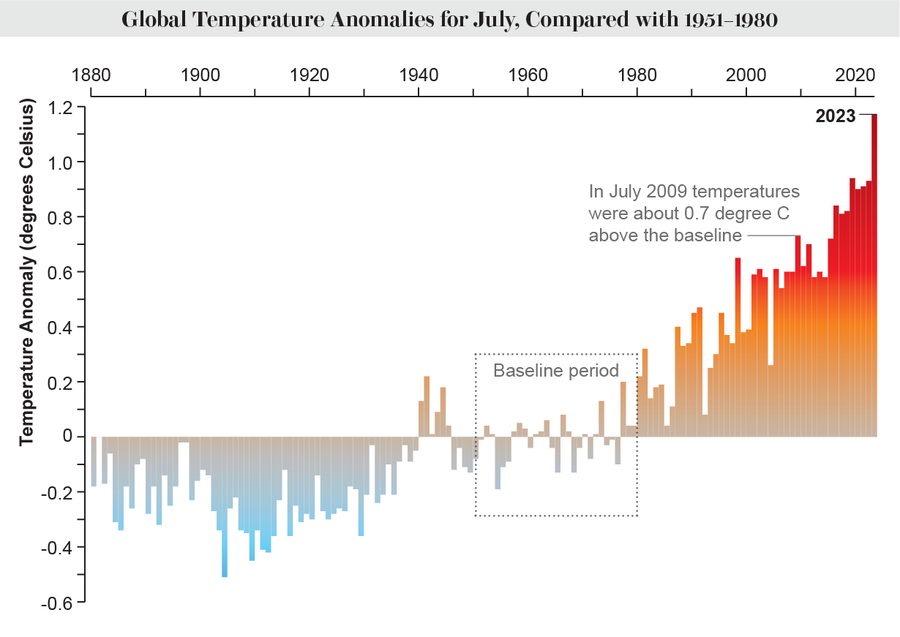

The WMO and C3S found that the first three weeks of this month were the hottest three-week period on record. The Leipzig University analysis determined that July 2023 will be 0.2 degree Celsius (about 0.4 degree Fahrenheit) warmer than the previous warmest July, which was in 2019, according to the database used. (Different climate agencies process global temperature records slightly differently, which can lead to some variations in temperature rankings.) This July follows the planet’s hottest June on record.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: Goddard Institute for Space Studies Surface Temperature Analysis, NASA

Because July is climatologically the hottest month of the year for the Earth as a whole, that makes July 2023 the hottest month since records have been kept and likely the hottest in 120,000 years, based on evidence of past temperatures found in ancient sediments and layers of ice, as well as on other paleoclimate records.

This July has seen record-breaking heat waves in several spots around the world, notably in the U.S. Southwest, Mexico, and China and around the Mediterranean. The records are primarily linked to overall rising global temperatures from the excess heat trapped in the atmosphere by humans burning fossil fuels. An analysis published on Monday by the World Weather Attribution group found that the heat waves in North America and Europe were “virtually impossible” without climate change. It also found that the heat wave in China was 50 times more likely to occur in our current warmer world. All three heat waves were hotter than they would have been without the boost from global warming.

El Niño, which developed in May, also boosts global temperatures—and this climate pattern’s combination with climate change makes it highly likely that more months this year will set records, according to Karsten Haustein, a Leipzig University climate scientist who conducted that institution’s analysis. The year as a whole will certainly rank among the hottest on record. Through June, it was the third warmest year to date (behind 2016, which featured a monster El Niño, and 2020), according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

A release from Leipzig University and another from the WMO and C3S both noted that July was about 1.5 degrees C (2.2 degrees F) above preindustrial levels, the warming limit countries have agreed to strive for under the Paris climate accord. That does not mean the world has passed that point permanently—overall the planet has warmed by about 1.2 degrees C (2.2 degrees F) since preindustrial times—but it is well on its way to doing so without immediate and significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

“The extreme weather which has affected many millions of people in July is unfortunately the harsh reality of climate change and a foretaste of the future,” said the WMO’s secretary-general Petteri Taalas in the WMO-C3S press release. “The need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is more urgent than ever before. Climate action is not a luxury but a must.”