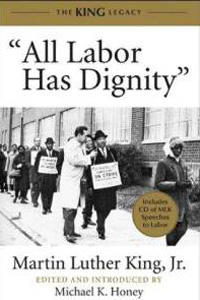

'All Labor Has Dignity': Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Fight for Economic Justice

Beacon Press

While researching at the Martin Luther King Center in Atlanta in 1992, Washington University professor Michael Honey found an inconspicuous folder marked "King's Labor Speeches." He opened it, and found a trove of King's addresses to labor unions and workers' rights coalitions—most of which had never been published.

This discovery led to "All Labor Has Dignity": King's Speeches on Labor, a collection edited by Honey and released in January by Beacon Press as part of their "King Legacy" series. The book shows an eerily prescient Dr. King, a clear-eyed visionary who speaks prophetically about the host of issues facing our nation today. In the eloquent, mythic language for which he is famous, King lambastes economic forces growing the gap between rich and poor, the massive tax resources used for war spending while domestic programs languished, and the knee-jerk demonizing of progressive social reform as "communist." He even criticizes the conservative senators—he calls them "Neanderthals"—who abused their filibuster privilege to block meaningful legislative change.

The collection demonstrates that historical considerations of Dr. King's contributions have overlooked his dogged dedication to the organized labor movement, and his fight on behalf of the working poor across racial divides. I spoke with Honey about King's work for workers' rights, the historical context of the speeches, and the relevance of King's conclusions to ongoing 21st-century American labor disputes.

How do these speeches collected here help us reevaluate King's legacy?

The book contains 15 different documents from 1957 to 1968, and they all present a somewhat different side of King that most people don't know about. Almost all of these speeches are unknown to the general public. Until recently, King's economic justice platform and his relationship with workers and unions has been an almost entirely neglected topic.

MORE INTERVIEWS:

Eleanor Barkhorn: How Timothy Keller Spreads the Gospel in New York City, and Beyond

Eleanor Barkhorn: Behind the Scenes at the Oscars: An Interview With Art Streiber

Douglas Gorney: Dreams From Africa: Exploring Barack Obama's Kenyan Roots

The civil rights movement was not just about civil rights—it was about human rights, and that means labor rights. The book is really about a period when King was trying to use the momentum of the civil rights movement to help the labor movement, the cause of public employee workers, and people in the service economy. And those are the areas where unions have grown tremendously in the last 20 or 30 years—in part because of Dr. King's sacrifice in Memphis.

Your collection shows King's systematic, concerted effort to yoke the predominately black civil rights movement with the predominately white, and sometimes socially conservative, labor movement. Why was this so important to him?

You have to ask: Why is he making these speeches in the first place? At that time in our history, there were a lot of very strong unions. He's asking them to donate money to the civil rights movement, which was an emerging movement, and he makes an interesting plea: You have a lot more power than we do, but we have the moral agenda—and the attention of the nation that you're losing. The business community and the media had been propagating this idea of big labor and union bosses, separating the unions from the workers, making them appear to be corrupt. And there were some corrupt unions. And some unions that were not only ignoring people of color, but totally excluding them. King wanted to convince the unions that the civil rights movement was not only important on its own—but that its success was crucial to the labor movement's success, too.

In a 1968 speech, King asks: "What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn't earn enough money to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee?" Had he started to feel that race reform was doomed without economic reform, and vice versa?

He did say that the civil rights that we'd attained from Brown vs. Board of Education to the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts were a remarkable change, but after that he really did emphasize economic issues. The urban areas were exploding all across the country. There were riots, police brutality, and National Guard occupation of black communities. The fact was, in the urban areas, civil rights didn't do anything to change the economic situation for the mass of working class people. Those were people that should have had jobs and union wages, who should have been advancing themselves. Instead, factories were shutting down. Jobs were being shipped overseas. The urban areas were being stripped of all economic activities. It was like stranding the millions of people who'd migrated to the cities for jobs. So, without an economic program—yes, that's what he was saying—the civil rights we've gained won't be meaningful for most people.

From "All Labor Has Dignity," March 18, 1968

Many of these speeches criticize the robustness of the American war machine. King is widely known as a Pacifist and a practitioner of non-violence, a student of Gandhi, but do these speeches give new dimensionality to his critique of violence?

There's a speech in here, given in 1962, where he says: "There are three major social evils in our world today: the evil of war, the evil of economic justice, and the evil of racial injustice." He goes on to show how these things are linked together, and gives a similar critique throughout the book. He particularly links the problems of poverty and economic injustice to the continuing escalation of war and foreign military intervention—you have to remember, he was giving these speeches in the context of the American invasion of Latin American countries, Vietnam, and the mass bombing in Indo-China. Sure, these efforts created some American jobs, but they also wreaked havoc all over the world.

What he's saying is this: militarism is not the way to economic prosperity for people in the United States. He saw it as a moral abomination that the U.S. was using its power this way in the world. And he thought it was also creating a nightmare at home.

The speeches, and your notes in the book, demonstrate that King often battled accusations that he was Communist—something of an elided historical fact.

The big campaign in the South was to frighten away middle-class, white support by calling King a Communist. Anybody who worked on civil rights was called a Communist. And some were. But King was of the opinion that if somebody sincerely supported the civil rights movement, they had a right to their political opinions. He wasn't going to turn people away who wanted to work seriously for justice because someone called them a Communist. He was always under attack for that.

In one speech, King invokes the biblical parable of Lazarus and the rich man Dives—like Dives, he says, America will go to hell if it turns its back on the poor. I was amazed by this—in our current political atmosphere, saying "America's going to hell" would be off-limits to any mainstream figure.

It was off limits then! King had reached a point in his life where he felt it was more important to speak the truth, even if it condemned him to death. It wasn't acceptable for anyone to say what he was saying. You didn't see very many civil rights leaders making linkages between racism, poverty—condemning the nation for what it was doing in moral terms, and in a prophetic rhetorical style. I don't think you can find as scathing an indictment of the United States in the rhetoric of any mainstream person at that time. But he wasn't speaking that way because it was acceptable—he was doing it because it was unacceptable, and he felt he had to speak the truth, and he felt his time was running out.

From "All Labor Has Dignity," March 18, 1968

King was working on an important Poor People's Campaign in New York City in early 1968. Why did he leave for Memphis?

The sanitation strike was reaching a crucial point, where the workers could possibly lose. They'd been holding mass meetings every day for over a month in different churches around the city. They'd been having picket lines two times a day. Marches downtown, every day. 1,200 workers on strike, for well over a month. They were running out of food. They were losing their homes, their automobiles.

The black community was in strong support of the strike. The AFL-CIO was supporting the strike. But they had a totally intransigent mayor, a fiscal conservative who was totally against unions. He wanted the city to spend less, and he wanted to take that out of the backs of workers. So you had this confrontation between labor and civil rights on the one hand, and fiscal conservatism and anti-unionism on the other. The strikers felt they weren't getting any attention, and that it was a really important battle—and that's why they brought King in.

How could he not go to Memphis? Here was a good example of local people organizing around the very issues he was trying to mobilize the country around. So, his staff told him he shouldn't go—but he went against their advice.

In the "Mountaintop" speech, the speech given in Memphis, King seems aware of the imminent threat of violence against his person, saying, claiming that while "longevity has its place," he would prefer to pursue his work than be assured safety. The whole coda of the speech is a meditation on danger and the transience of life. What was it about the climate in Memphis that had King so aware of the danger of his being there?

When he flew to Memphis the day before he gave that speech, there was a bomb threat. They had to hold the plane in Atlanta while they searched for bombs, and it was because he was on the plane. He'd told his family before he left Atlanta that someone was trying to kill him, and that they should be ready. We know from the House Committee on Assassination that there was a reward of $50,000 put up by some businessmen in St. Louis for somebody to kill him. He definitely had premonitions that it could very well happen at any time. He was always being attacked by the right wing, neo-Nazis, and segregationists. But when he came out against the war, the opposition to him went right up the ranks to the President of the United States, and certainly the FBI—which had been trying to destroy his career since 1963, at least. The whole atmosphere around King was tainted by real hostility to what he was saying and doing.

Then, to go to Memphis in the middle of a very tense situation, where there'd been a strike that had been going on for nearly 60 days, where police had attacked people repeatedly, and several people had been killed ... it was a very violent atmosphere. So all of that brought out that meditation on April 3rd. These were the things that were flashing through his mind.

Of the speeches in the book, is there one you feel best captures the spirit of King's labor and economic effort, the way his "I Have a Dream" speech captured his civil rights work?

The one that I like the best, I guess, is the one the book is named for: "All Labor Has Dignity," a speech to the Memphis sanitation workers. It's not a scripted speech—and it's marked by constant cheers and uproarious approval, and chanting. He's talking straight from the heart—it's King at his best. He talks about the problem of two Americas, one poor and one rich. The gulf between people with inordinate, superfluous wealth and the people suffering in abject, deadening poverty. He talks about the working poor—people who work what he calls "full-time jobs at part-time wages." He talks about hospital workers being as important as the physician, and sanitation workers being as important as the doctor. How labor is not menial until you're not getting adequate wages—all jobs are important. The question is do you have dignity, and respect, and a decent livelihood, based on what you do? I just think it's a marvelous speech, and it deals with a lot of the issues we're still dealing with today.

What might King have thought of our current political climate, especially in regards to our economic and labor practices?

He'd be aghast. And appalled. He had high hopes for the United States. He was really focusing on the promise of the American Revolution, and "all people are created equal," and the inherent rights we have. He would often say—and he says in these speeches—that the promise of America is equality, and he believed in that until he died. He really saw the U. S. as a place of great hope. I think in some of his sharpest criticisms of the U. S. in '67 and '68, he's incredibly disappointed with the way things are going. If he were transported in time 40 years after his death to see what's happening now—he'd be shocked and appalled at the backward direction of the thinking of so many people. How so many people fail to take in the lessons and experiences of history. We're in a pretty sad time—a lot of the unions King fought for have been destroyed, and the civil rights movement is kind of in abeyance in many ways. If he was here now, he'd be really searching—how do we rebuild a movement that brings everybody in? And really, that's the challenge before us.