Architecture doesn’t generally sneak up on you. You look for it because you’ve seen a castle in photos, crossed an ocean for a cathedral, or been assured of a house’s masterpiece status. But on a stroll through the Xochimilco neighborhood in Oaxaca, my wife nods at the side of the street and says: “What’s that?” It’s not a building that draws her eye, exactly, but the suggestion of one: a swooping stone wall, trimmed with white like a calligrapher’s stroke, that dips beneath a leaning tree and gaps at a narrow doorway. A sign informs us that it’s the public library for children, and that it’s named for Jorge Luis Borges because it also includes a library for the blind.

We step through the portal and find ourselves in a foyer of delightful strangeness. A round hole in the ceiling forms a column of light (or rain). The floor inclines down a gentle hill. A wall of puckered, iridescent tiles, ranging from cliff red to ocean blue, evokes a topo map that’s been cut into squares and scrambled. Through a second opening, an outdoor pathway curves down the terraced slope alongside a low, snaking white building scored with ribbon windows. A long, bending canopy shades openings with saloon doors. Here and there, well-placed holes allow the hog plum trees that dotted the vacant site before construction to keep growing through the roof undisturbed: Inside, carefully diffused daylight washes over long wooden tables set at a kindergartner’s height. The ceiling is stenciled with black-and-white children’s drawings that brings to mind a crew of miniature Tiepolos supine on scaffolding, doodling upward. (That’s not how it was done.) I have never seen young kids treated with such a mixture of empathy, seriousness, and architectural verve. It’s as if Le Corbusier had come to Mexico and discovered joy.

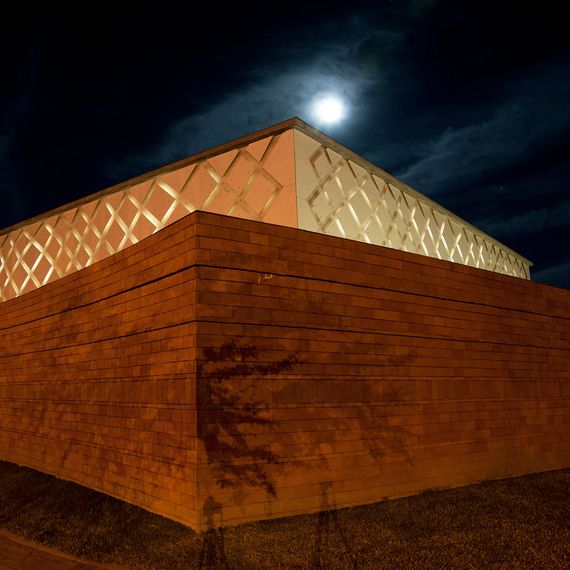

Santibañez’s children’s library in Oaxaca, seen from the street.

An oculus in the foyer creates columns of sun and rain.

Highly textured tile.

The building winds through the sloping terrain to make way for preexisting trees.

Ribbon windows and a ceiling decorated with kids’ drawings.

Santibañez’s children’s library in Oaxaca, seen from the street.

An oculus in the foyer creates columns of sun and rain.

Highly textured tile.

The building winds through the sloping terrain to make way for preexisting trees.

Ribbon windows and a ceiling decorated with kids’ drawings.

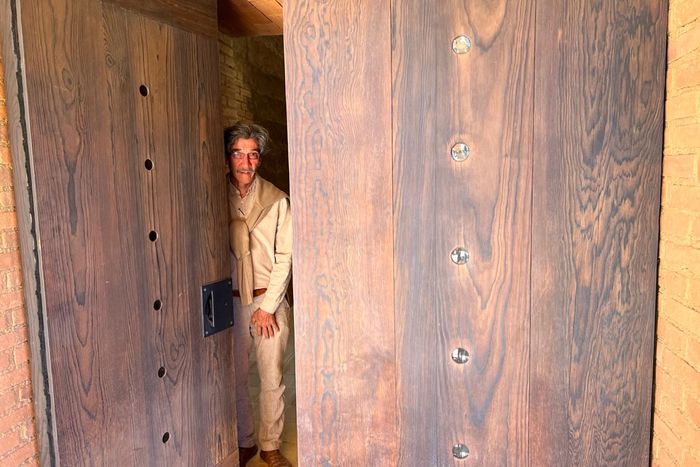

Chances are you’ve never heard of Juan José Santibañez, the man who designed this exquisite library, or his firm, Arquitectos Artesanos. Far from the international circuit and little known even in Mexico, Santibañez believes deeply in rooting himself in the fertile highlands of the country’s southeast. “Architecture belongs to a place,” he says, when I eventually meet him. “I could never work anywhere but here.” A rangy, soft-spoken 65-year-old with a manner that mixes slight sheepishness and quiet pride, he has never bothered to learn English, employ a publicist, enter competitions, or grow his firm beyond a staff of nine, including himself, his wife, and two adult daughters. His catalogue of works is slender. And yet, in his understated way, he has had an outsize impact on this ravishing, sophisticated city of 300,000 and its vast hilly region of Indigenous villages. Tourists make pilgrimages to the Textile Museum, which he and a team of restoration architects carved out of a crumbling warren of houses erected and neglected over 300 years. Students from all over the area converge on the La Salle University campus that he designed from scratch, an astonishing 30 buildings in all. He has almost single-handedly revived ancient construction techniques in the area, created a market for artisanal brickmakers from miles around, and proven that genuine sustainability can be a source of pleasure, not just a grimly abstemious virtue. His buildings have a soft, tactile beauty, derived from the warm hues of fibrous mud, glossy plaster, charred wood, and hand-formed brick. Rainwater plashes down zigzagging channels of black steel. Breezes and daylight slip through clerestory openings, and thick earthen walls keep temperatures constant. Santibañez makes judicious use of concrete, steel, and glass where necessary, but for the most part, his architecture springs from the soil and rock it stands on and ends up suffused with serenity and delight.

When I get in touch with him, he suggests starting our tour of his work with a client’s private home a few miles away in the town of Tlalixtac de Cabrera. I’m more interested in his public projects than in a deluxe suburban keep, but he gently insists. “This project distills everything I’ve been working on for decades,” he says, steering his aging hatchback along a valley road lined with agave plantations and stretches of chaotic sprawl. Although he received his formal education at the Popular Autonomous University of the State of Puebla, he tells me that he really learned his craft in the 1990s, after he returned to his native city, Huajuapan de León, about 100 miles from Oaxaca. There, he designed a compound of small houses on a rural ranch, one for himself and his wife Edith, and two for friends. Using that as a base, he began touring the area’s hill towns, studying adobe construction techniques that had endured from pre-Hispanic times but were now vanishing under pressure from earthquakes, abandonment, and modernization. He found a kind of ecstasy in cataloging the few modest homes that still stood and salvaging an unwritten repository of architectural knowledge.

“Vernacular architecture supplies lessons that help us develop our individuality because it contains knowledge, common sense and mystical energy,” he wrote in a letter to his daughter María, who now works as a designer in his studio. “In its idioms, it teaches us to recognize nature’s codes, to identify the creatures that share our space, to read its colors, movements, rhythms, sounds, light, nights, songs, and silence.”

Research on those traditions has thrived in recent years. The 87-year-old architect and designer Oscar Hagerman has spent decades arguing that popular traditions in Mexico are an inexhaustible source of authenticity, soul, and radical sustainability. Still, preserving them remains a losing battle. Whenever a town undertakes spasmodic bouts of rebuilding, trucks arrive bearing cement blocks, rebar, and bags of dry concrete that villagers use to repair crumbling walls or add extra rooms. Those industrial products aren’t always compatible with handmade structures, though, because concrete and steel are more rigid than organic materials, and have different thermal properties, so homes that get the wrong kind of upgrades wind up even more vulnerable to cracking and collapse. “They don’t teach this stuff in school,” he tells me. “I learned to stick to ancestral knowledge, and I pay attention to what the old folks do.”

He also persuaded them to listen to him. In each town Santibañez visited, he plugged a VCR into whatever TV set was available, showed a montage of photos he had assembled , and pleaded with Zapotec and Mixtec-speaking villagers not to gut their own heritage. “When I arrived in one town, they took me into a stone house with a thatch roof,” he recounts. “The women stood in the front, the men in the back, and they told me they wanted to tear it down and replace it with industrial materials. I didn’t know what to say, but I thought of Robin Williams in Dead Poets Society, and I yelled ‘No!’ I said, ‘Who’s the oldest person here?’ They pointed to an old lady and I said, ‘Okay, should we kill her? That’s what you’re proposing. This house is filled with the sweat and the fingerprints of your grandparents.’ They understood, and we saved the house.”

In a limited way, his efforts paid off. A group of 16 women from the town of San Miguel Amatitlán asked for his help in building their homes — cheaply, authentically, and with their own hands — a project that eventually made an appearance in the 2016 Venice Biennale. Sweat is a big part of his philosophy; later, he sends me a video clip of his younger self on a job site, long hair tied back in a ponytail, plunging his arms into a wheelbarrow full of mud and straw. The message is clear: Architects should get their hands dirty, not just hand off drawings and let contractors figure out how to realize them. “I found a way of building that was both innocent and audacious,” he says.

The glorification of rustic traditions has a fine if erratic history. Mexican architects have rediscovered the virtues of compacted earth, known as tapial. Tatiana Bilbao combined vernacular techniques with Spartan modernism for a summer house in Jalisco; the firm GOMA even created a fake-rammed-earth house made of concrete, a style you might think of as peasant brutalism. To some extent, cultivated parochialism has become a global phenomenon. In 1983, the critic Kenneth Frampton wrote an immensely influential paper advocating locally inspired architecture. “Everywhere throughout the world, one finds the same bad movie, the same slot machines, the same plastic or aluminum atrocities,” Frampton complained. As an antidote, he proposed a movement he called critical regionalism, an approach that planted contemporary architecture in the soil and customs of a particular place. Among his paragons were the Catalan architect Ricardo Bofill and the Mexican Luís Barragán, who died in 1988 but whose fuchsia walls and exquisitely placed windows have come to embody a quintessence of Mexican-ness in the Instagram age. Crucially, Frampton took pains to separate critical regionalism from “the simplistic evocation of a sentimental or ironic vernacular.” Reproducing, preserving, and imitating folk traditions was, he suggested, an antiquarian’s errand, futile and sentimental.

I thought of that distinction when I saw Santibañez’s own work, which is simultaneously rooted and inventive but neither nostalgic nor fashionable. In his hands, artisanal practices become a contemporary source of creativity, not just a UNESCO World Heritage form of picturesqueness. “He’s the foremost architect in Mexico who’s using the vernacular lexicon and bringing it into contemporary culture,” says Alejandro de Avila, the director of both Oaxaca’s Textile Museum and its Ethnobotanical Garden. Santibañez is less interested in copying ye olde styles than in adapting time-tested techniques for an architecture that is sensual, fresh, and deeply local. He shakes his head at the international circuit of celebrity architects who sprinkle their idiosyncrasies on cities all over the globe. “How can you drop a building here and then go drop the same building over there when you don’t know anything about the people, the soil, the climate, or the culture?” he says. (In one sense, he has it relatively easy: Oaxaca’s nearly paradisiacal year-round climate and high altitude makes natural heating and cooling an obvious choice; on the other hand, the region is disastrously earthquake-prone.)

In recent years, Frampton’s idea of critical regionalism has gotten an update in the much-laureled work of, say, Francis Keré. Born in Burkina Faso but based for decades in Berlin, Keré won the Pritzker Prize on the strength of handmade school buildings he designed for his native village of Gando. Wang Shu, the co-founder of Amateur Architecture Studio with his wife Lu Wenyu, won the same prize in 2012 for rural projects inspired by Chinese vernacular styles. Santibañez operates in a similar vein and at a comparable level of excellence. But he has no promotional network and no gift for self-aggrandizement. In any case, exporting his talents to London or New York would mean adjusting to a completely different set of conditions and constraints, like the high cost of labor, extremes of heat and cold, and a global supply chain of processed materials. In a northern metropolis, design starts with ingredients that are fabricated on distant continents: steel from China, glass from Germany, façade panels from the Philippines, and concrete that, wherever it is mixed, pumps out gases that encircle the globe. The fact that someone like Santibañez doesn’t naturally fit into that industrial megalopolitan frame is our loss, not his: It’s a measure of an impoverished architectural culture.

If he doesn’t feel limited by a small city, or a state that has roughly the land area of Indiana and two-thirds the population, that’s partly because there’s plenty of cosmopolitanism to sustain him there. Some years ago, he moved from Huajuapan to Oaxaca, joining a coterie of intellectuals and artists who help give the city its vibrancy. The project he drives me to is a rich person’s version of a poor person’s house, and the owners shuttle back and forth to Mexico City: Manuel de Esesarte is a former member of parliament and mayor of Oaxaca; his wife, Rocío Ranz, runs a furniture company. The spatial organization of society in Oaxaca is the reverse of the Hollywood Hills. Here, it’s the poor who live perched on mountain slopes, and the rich who occupy the flatlands where water gathers and roads are straight. A wealthy purchaser couldn’t even find such an expansive plot up in the mountains, Santibañez tells me, because the highlands are mostly held in common, not chopped up into private property. There’s no one to buy it from. I’m not sure that’s accurate, but he seems pleased by the belief.

My first impression of the compound, located in a breezy field with intimate views of the mountains, is that Santibañez is a master of the windowless wall. The perimeter looks almost edible, as if it were achieved by stacking brownies. Instead, it’s made of fibrous dirt mixed with pine needles and shaped by hand into blocks that are separated by terra-cotta shingles and left to dry in the sun. That sounds straightforward, but it’s precision work. Add too much or too little water, treat the fit sloppily, or stint on the time each layer takes to harden, and you’ll be left with a mound of dust instead of a shapely shell that will defy rain and stand up to tremors. (Ancient earth-and-stone structures have endured all kinds of punishment, and Peru’s building code includes guidelines on how to achieve that kind of longevity.)

Through the heavy wooden doors, we gaze down a long hallway crowned with daylight that shoots towards a mysterious scarlet square. I can’t quite make out what I’m looking at: a minimalist painting? The mouth of a furnace? “That’s the heart of the house,” Santibañez explains. “Indigenous people describe a home like a body. It has a heart, a spine, skin, and a respiratory system, and you have to keep it all in balance.”

Hand-formed blocks of clay-based earth mixed with pine needles at the Esesarte house

The hallway leading to “the heart of the house.”

The meditation room.

A sunroom.

Artwork set into the wall hints at the earthen bricks that support the house.

Hand-formed blocks of clay-based earth mixed with pine needles at the Esesarte house

The hallway leading to “the heart of the house.”

The meditation room.

A sunroom.

Artwork set into the wall hints at the earthen bricks that support the house.

As we get closer, the rough earthen hallway gives way to a tunnel of glossy egg-yolk yellow, and beyond that is a red-walled meditation room with a sunken floor covered in white sand and high windows that dust the space with celestial light. Ranz had wanted to emblazon one wall with a cross. Her adult children rebelled, and the chamber remains nondenominationally sublime.

As we proceed through generous rooms that face toward mountain views Santibañez keeps coming back to the house as a representation of the body. When a human hand has shaped every brick, slat, and block, then each is similar but unique and unrepeatable, he says — just like us. To him, the mottled, uneven surface, now lustrous, now matte, makes architecture alive because it resembles human skin, the surface of the earth, or the bark of a tree. The pattern of cracks and protrusions echo one another at every scale. One of the unpolished ceramic floor tiles bears the pawprints of a large dog that must have stepped into a mold full of wet clay.

The same craving for the irregular imbues every surface and every piece of hardware. The steel hood over the fireplace is stained with blotches of plaster and red paint to create an abstract artwork. A set of charred wood sliding doors hides the enormous television set. A sculptural artwork sunken into the wall is effectively a square of parched earth, its cracks naturally producing a rhythmic design like a landscape of canyons and coulees seen from a plane.

The little red chamber may be the house’s heart, but if I had to locate its personality, I would choose the covered patio adjoining the bedrooms. (To Santibañez, it’s the lungs.) The elements meet in this airy cloister. Fresh air and daylight cascade through hidden clerestory openings around a vault of wooden slats. A sky-blue glossy partition meets the ground at a crust of irregular terra-cotta tiles, like a cracked and burnished desert. Beneath the fissures, water runs across a magma-red floor. This space is a refined, polychrome composition made mostly of materials that can be gathered along a vigorous hike. It embraces urban luxury without abandoning its rural roots—much like the exquisite vegetal-dye weaves that have made the region famous. The house’s progression of hues, from dirt-brown through ochre, and yellow to deep red and indigo, aligns with the colors of Oaxacan textiles.

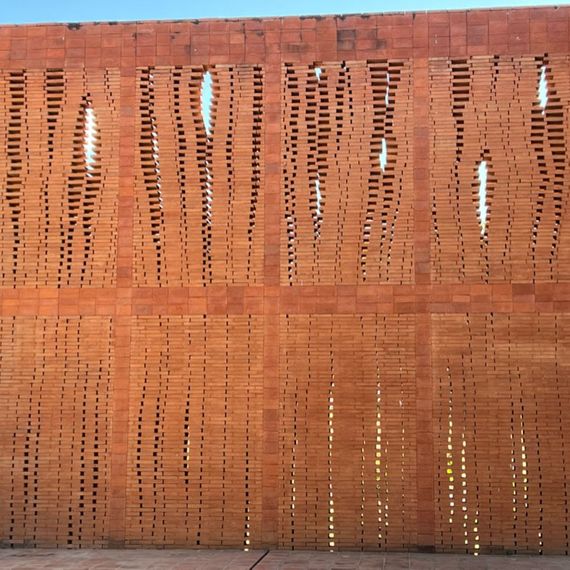

The connection between weaving and architecture isn’t casual. Santibañez’s most visible work is the main courtyard of the Textile Museum, a double-height red-brick-and-shingle screen vibrating with shadows, voids, and triangles. It’s the sort of spot that makes visitors reach for their cameras and attune their eye to a complex surface even before getting a look at the treasures inside. The brick screen — celosia, in Spanish — was one of the last elements to fall into place, and both the architect and his client, María Isabel Grañén Porrúa (the director of the foundation that funds the museum), were getting worried. “I kept looking at the textiles every day, and it was dazzling, but I couldn’t figure out a way to capture them that wasn’t just imitation,” Santibañez says. At this point, the stories vary. Grañén says she told him to spend a Sunday at the spectacularly ruined city of Mitla, where the remaining walls are alive with patterned facades. Santibañez says he went on a hike in the country. “It started to rain, and I took refuge on a red-earth cliff, right by a column of ants. I looked at the ants closely and saw triangles in their eyes, and I thought that was amazing. A few hours later, I talked to María Isabel, who had been looking at a book of Anni Albers textiles full of triangles. So we arrived at the same solution at the same time, but in completely different ways. And of course Mixtec textiles are full of triangles, too.”

At Mitla, builders reproduced pre-Hispanic textiles in architectural form, using stone in place of thread. A millennium later, the same geometric motifs endure in the elaborate carpets woven in the nearby town of Teotitlán del Valle. Santibañez’s screen represents another turn of the influence wheel: It’s architecture informed by textiles that represent architecture that imitated textiles.

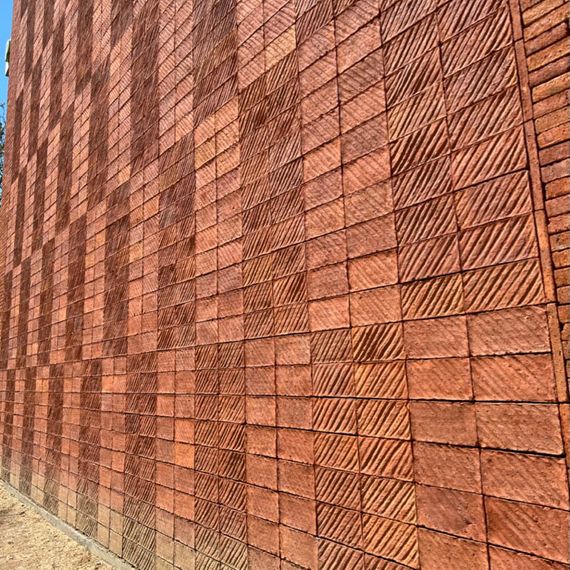

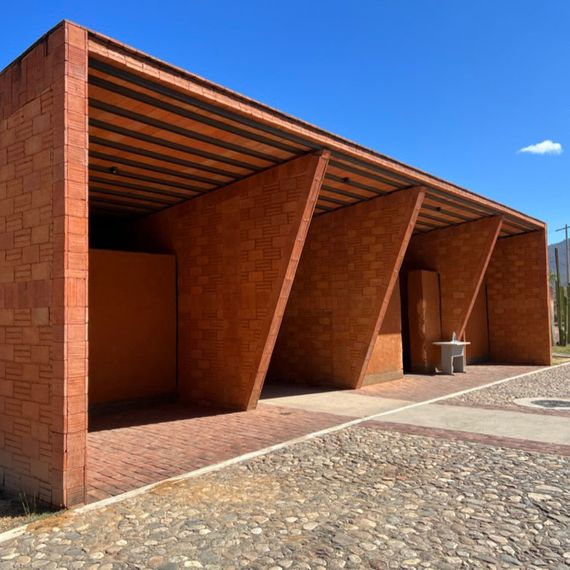

Whether Santibañez’s celosia originates in an entomological hallucination, a reference to the European avant-garde, or the legacy of anonymous weavers, what makes all that warmth and intricacy possible at the scale of a building is the fabricating and laying bricks, a craft that is both intensely local and worldwide. In the U.S., as in the U.K., brick long ago came to be seen as humble, standardized stuff, the basic element of mills, power plants, and housing projects. Mexican architects — a few, anyway — have treated hand-formed chunks of baked earth more lovingly, celebrating their irregularities and versatility. Perhaps the ultimate demonstration of that skill and affection is Carlos Mijares’s Pantheon Chapel in Jungapeo from the 1980s, a fugue of vaults and arches made of handmade brick. Santibañez is no slouch in that department, either. The campus he designed for a private college, La Salle University, is a vast showcase of virtuoso brickwork. One façade with diagonal striations seems to come alive as you walk past and see all the tiny parallel shadows shift. On other buildings, bricks form runnels, ramps, serrations, and steps. A high wall at one end of a workshop complex appears to be dismantling itself. Staggered bricks start to pull away from each other, leaving gaps and teeth as in an opened zipper. Depending on how you look at it, the wall appears to be coming apart at the seams, blowing like a curtain, or turning into lace.

As with the house in Tlalixtac, Santibañez has organized the campus along a linear axis, with classrooms staggered, not quite symmetrically, on either side like a fish’s scales. Nothing about the design is precious. Budgets were tight, and so were seismic and construction codes. Industrial products appear, but always in the background; for the most part, several thousand students who commute from the surrounding countryside do their learning in a complex that is hand-built by their neighbors and designed with a care they can feel even before they consciously register it. Banded skylights fill the gym with diffuse sunshine. In the glowing library, a mobile of painted panels by local artist José Luis Garcia dangles from a lightwell like a haloed chandelier. A row of offices glimmers warmly, thanks to pale brick, pale wood dividers, and pale tiles on the floor. Even a freestanding set of restrooms with a breezeway down the middle and a shade canopy on top gets the deluxe treatment, turning it into an aerated sculpture.

Once you start to think about the delicacy and inventiveness of simple materials, you see it popping up everywhere, sometimes in deceptively improvisational form. Santibañez wanted to shade a set of glass-walled dance studios with a compacted-earth wall, but the construction schedule didn’t allow for long drying times. To speed up the process, he had masons aerate the wall with gaps formed by curved shingles. The result is a perimeter dotted with terra-cotta-lidded eyes — or maybe they’re terra-cotta-lipped mouths — a wall that winks, breathes, gazes, and puckers for a kiss.

Santibañez is a serious man with an impish streak that he expresses more in work than in words. A small windowless brick box that you might mistake for a particularly gracious machine shed is, in fact, a camera obscura: Once you enter, shut the door, and get used to the dark, you notice that a pinhole in the ceiling and another at eye level project reversed images onto the interior surfaces. While we’re inside, he keeps hoping that a plane will cross over the sun so that we can see it fly backwards along the floor. The building is more than a folly, though; it’s intended to demonstrate his theory that a buried chamber he once came across in a village, and later saw illustrated in a Zapotec codex, functioned as a way to pinpoint feast days and propitious times for a harvest.

So what’s a reconstructed pre-Christian observatory doing at the center of a Catholic college? A knot of contradictions ties together Oaxaca’s architecture and money flows, its local traditions and global modernity, private initiatives and public service. The city is an intensely political place. In any given month, striking workers, unemployed students, representatives of Indigenous communities, anti-sexual violence activists, feminist collectives, and other groups take turns occupying the streets around the Zócalo with tents and posters. A violent teachers’ strike in 2006 galvanized a women’s protest movement and helped artisans’ collectives evolve from loose associations into political forces. But the images of burning buses also scared away the tourists who provide the crafts’ major market. For all the populist rhetoric surrounding Oaxaca’s native arts, their flourishing has depended largely on a few cultivated individuals and a single tycoon. The painter Francisco Toledo (who died in 2019) founded a clutch of the city’s major cultural organizations: a graphic-arts institute, a photography institute, a contemporary art museum, an arts center with studio space in the nearby town of San Agustín Etla. To create the ethnobotanical garden in the grounds of a former Dominican monastery, he teamed up with the botanist Alejando de Avila. Many of these institutions depend on the Alfredo Harp Hélu Foundation, funded by the banking and telecom billionaire. The foundation, directed by Harp’s ultra-erudite wife, Isabel Grañén, a scholar of 16th century prints and books, sustains the region’s fragile cultural plenty practically on its own. It was Grañén who picked Santibañez to design the children’s library, with the proviso that he not uproot any trees. Then she asked him to work on the Textile Museum. And when the time came to create La Salle University, she didn’t hesitate to commission not just a building or two, but an entire campus from scratch. “When Juan José is working on a project, he practically lives on the site, he’s there every day, talking to the builders and fully connected to it. He pours his body and soul into it. You can’t say the same about many other architects.” The upshot is that the self-effacing champion of the vernacular owes his career to one of Mexico’s richest families.

What links this tiny club of scholars, artists, and billionaires, de Avila tells me, is the concept of comunalidad, the communitarian principle that recognizes shared values and interests beyond political divisions. “Artists like Toledo, Rodolfo Nieto, and Rufino Tamayo felt a responsibility toward the public good, and I see Juan José following in that tradition,” de Avila says. That, surely, is one reason a city the size of Newark enjoys a cultural life as rich as some European capitals. Comunalidad is not just an abstraction; it’s reflected in architectural choices. “We wanted to make it possible for students from the state of Oaxaca not to emigrate to Mexico City or Oaxaca, but to pursue their educations here, close to home,” Grañén says. “So Juan José designed a university at the human scale, without any intimidating marble monuments.” It’s true: The buildings are airy, permeable, unfussy, and generously shaded against the punishing sun. They welcome students without showiness or fanfare.

It’s a beautiful thing to see the fruits of capital supporting the ultralocal labor of a million nimble hands. One of the ironic offspring of these strange bedfellows is a Harp Hélu Foundation’s campaign against haggling over the price of handicrafts. Negotiating with makers amounts to an “injustice” that can range from “annoying” to “humiliating” — declares a philanthropic organization created and fed by the global market. You might read that tension as hypocrisy; I see it as a form of virtuous flexibility that keeps looms clacking, printing presses churning, masons working, and Indigenous practices thriving. If Santibañez says he could only ever work in Oaxaca, it’s also because this magnetic and dynamic city is uniquely set up for him to coax something fresh and new out of tissue that had seemed spent.